Book Details:

Book Details:

• Author: Emanuel Tov

• Category: Academic, Biblical Language

• Publisher: Fortress Press (2012)

• Format: hardcover

• Page Count: 512

• ISBN#: 9780800696641

• List Price: $90.00

• Rating: Recommended

Review:

Reading Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible by Emanuel Tov was both a joy and a challenge. I thoroughly enjoyed immersing myself in the world of the Hebrew Bible. Ancient manuscripts, Dead Sea Scroll finds, ancient versions, textual variants — all of these things stir the Bible-geek in me. At the same time, the state of current scholarship with regard to the Old Testament text can be a bit troubling to an evangelical Christian. While the New Testament stands affirmed by numerous manuscript discoveries to the extent that almost all textual critics can agree on the vast majority of the minute details of the text, the same cannot be said for the Hebrew Old Testament.

Emanuel Tov takes readers of all scholastic levels by the hand as he surveys the field of Old Testament textual criticism. This third edition of his classic textbook, explains things for the novice and scholar alike. Careful footnotes and innumerable bibliographic entries will impress the scholar, while charts, graphs and numerous glossaries keep the would-be scholar feeling like he is getting somewhere. I have no problem admitting that I am one of the would-be scholars, with barely a year of Hebrew under my belt. Yet I was able to work my way through this book, becoming sharper in my Hebrew and awakening to the many facets of the intriguing study of OT textual criticism.

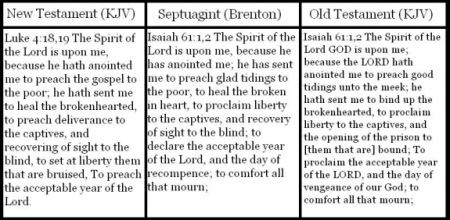

Tov has departed from a more traditional stance in his earlier versions, opting instead to follow the evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls and contemporary studies. He manages to keep away from a fatal skepticism, however, arguing that textual evaluation still has merit. The aim is still to recover the earliest possible text, but the recognition that there are often two or three competing literary editions of the text complicate the matter. An example would be the different editions of Jeremiah, with the Septuagint (LXX) Greek version differing drastically from the Hebrew Masoretic Text (MT). 1 Samuel provides another example with a Dead Sea Scroll offering perhaps a third different competing literary edition. Tov points out the two very different versions of the story of David and Goliath and Hannah’s prayer as he expounds on the problem.

Rather than trying to solve each exegetical or specific textual problem, Tov aims to illustrate the challenges facing the would-be textual critic. He surveys the textual data, and reconstructs the history of the text – giving more attention to the accidents of history, such as the destruction of the Jewish state in A.D. 70, as weighing into the nature of the textual evidence we have. Rather than the Masoretic Text gradually gaining dominance, it was the de facto winner of the “text wars”. The LXX-style Hebrew texts (which the Dead Sea Scrolls and other finds have confirmed existed), were ignored by the Jews as Christianity had owned the LXX as its own. The Samaritans had their version of the Pentateuch, and the existence of a variety of other text forms, such as those found at Qumran (the DSS) were forgotten with the cessation of a normal state of existence for Jewish people. The Masoretic text found itself with little real competition and over the years came to be further refined and stable. I should clarify here, that this is not to downplay the Masoretic text, as it manifestly preserves very ancient readings, and Tov repeatedly affirms the remarkable tenacity of the MT. Instead, Tov is saying that the majority position the MT holds among the textual evidence and in the minds of the Jewish communities in the last 1800 years should not prejudice the scholar to consistently prefer MT readings. Tov in fact claims that text types, such as are commonly discussed in NT textual criticism, are largely irrelevant in dealing with the OT text. Internal considerations are key in textual evaluation. I will let Tov explain further:

Therefore, it is the choice of the most contextually appropriate reading that is the main task of the textual critic…. This procedure is as subjective as can be. Common sense, rather than textual theories, is the main guide, although abstract rules are sometimes also helpful. (pg. 280)

Tov’s textbook goes into glorious detail concerning all the orthographic features that make up paleo-Hebraic script, and the square Hebrew script we are familiar with. His knowledge is encyclopedic, to say the least. The numerous images of manuscripts that are included in the back of the book are invaluable. His discussion on the orthographic details of the text should convince even the most diehard traditionalists, that the vowel points and many of the accents were later additions to the text, inserted by the Masoretes. Some still defend the inspiration of the vowel points, but Tov’s explanation of numerous textual variants that flow from both a lack of vowel points and from the originality of paleo-Hebraic script (and the long development of the language and gradual changes in the alphabet, and etc.) close the door against such stick-in-the-mud thinking.

Tov’s book details the pros and cons of different Hebrew texts, as well as discussing electronic resources and new developments in the study of textual criticism. His work is immensely valuable to anyone interested in learning about textual criticism, and of course is required for any textual scholars seeking to do work in this field.

Tov doesn’t add a theology to his textual manual, however. And this is what is needed to navigate OT textual criticism. After having read Tov, I’m interested in seeing some of the better evangelical treatments of the textual problems of the Hebrew Bible. I believe we have nothing to fear in facing textual problems head on. Seeing different literary editions of the text can fill out our understanding of the underlying theology of the Bible as we have it. Some of the work of John H. Sailhamer illustrates this judicious use of contemporary scholarship concerning the literary strata of the text.

Tov’s book is not law, and he sufficiently qualifies his judgments. He stresses that textual criticism, especially for the Old Testament, is inherently subjective. It is an art. And those who don’t recognize that, are especially prone to error in this field. This book equips the student to exercise this art in the best possible way. Tov walks the reader through evaluating competing textual variants, and his study will furnish the careful reader with all the tools to develop their own approach to the text. Tov’s findings won’t erode the foundations of orthodox theology. I contend that they will strengthen it. As with NT textual criticism, paying attention to the textual details has unlooked-for and happy consequences. It strengthens exegesis, and allows for a greater insight into the meaning of the text. And it can build one’s faith.

Bible-geeks, aspiring scholars, teachers and students alike will benefit from this book. Understanding the current state of OT textual criticism puts many of the NT textual debates into perspective. Christians don’t know their Old Testaments well enough, and studying the text to this level is rare indeed. I encourage you to consider adding this book to your shelf, and making it a priority to think through the challenges surrounding the text of the Hebrew Bible.

Author Info:

Emanuel Tov is J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Editor-in-Chief of the Dead Sea Scrolls Publication Project. Among his many publications is The Greek and Hebrew Bible-Collected Essays on the Septuagint (1999).

Where to Buy:

• Christianbook.com

• Amazon

• direct from Fortress Press.

Disclaimer:

Disclaimer: This book was provided by Fortress Press. I was under no obligation to offer a favorable review.

Recently, Baker Books came out with a beautiful full color illustrated Bible handbook. I’ve enjoyed paging through this gem of a resource and am planning to post my review of it next week. When I came across the article it contained on Goliath’s height, I knew I’d have to share it with my blog audience. You’ll probably be as fascinated and intrigued by this article as I was.

Recently, Baker Books came out with a beautiful full color illustrated Bible handbook. I’ve enjoyed paging through this gem of a resource and am planning to post my review of it next week. When I came across the article it contained on Goliath’s height, I knew I’d have to share it with my blog audience. You’ll probably be as fascinated and intrigued by this article as I was.